The Rosenwald Schools: A Forgotten History of Educational Innovation

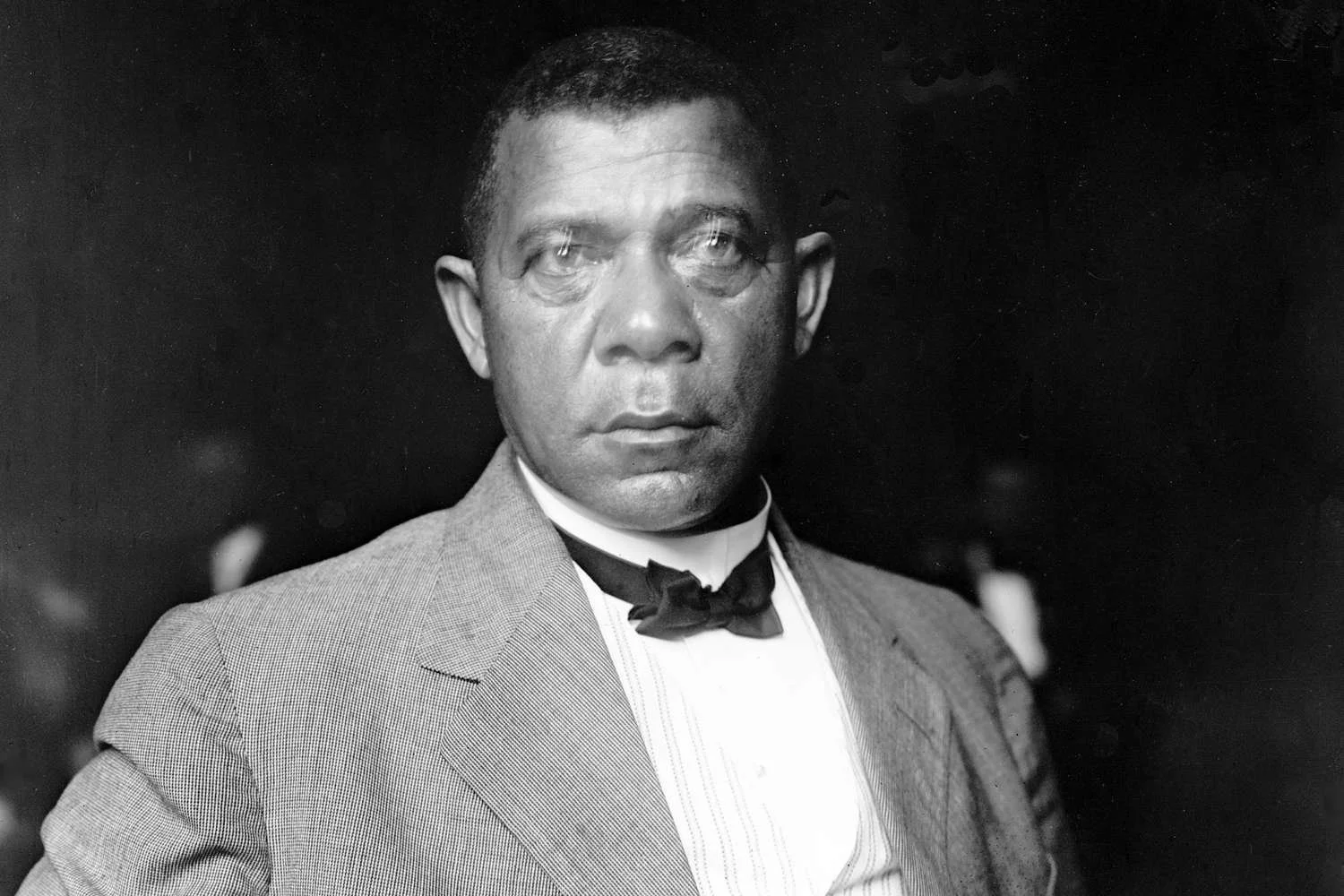

Booker T. Washington, major architect of Black education

Which major retailer was the first to invest heavily in building schools for poor Black children? Most people would guess Walmart, given the Walton family's well-known support of charter schools. But the answer is actually Sears.

Long before modern charter schools emerged, Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears & Roebuck, partnered with Booker T. Washington to fund what would become one of the most successful educational initiatives in American history.

The early twentieth century was brutal for Black Americans. In the South, where most lived, educational opportunities were virtually nonexistent. The schools that did exist for Black children were deliberately neglected—lacking basic supplies, adequate facilities, and qualified teachers.

The numbers tell the story. According to Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago research, Black children born in the South between 1880 and 1910 completed three fewer years of schooling than their white counterparts. Despite some absolute gains, Black students made no relative progress over this thirty-year period.

Faced with systematic exclusion, Black communities did what they had always done: they created their own solutions. Freedmen schools, community education collaboratives, and volunteer teachers from the North all played a role. But these efforts, while heroic, could never achieve the scale needed to make a lasting difference.

That changed in 1913.

The Rosenwald Partnership

Booker T. Washington approached Julius Rosenwald with a simple proposition: help Black families trapped by poverty and racism through education. Washington believed that while there were countless ways to address racial inequality, education was the most practical and powerful tool for fighting poverty.

Rosenwald agreed to fund a matching grant program for the construction of Black schools across the South. The partnership began with six schools near the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. By the time it ended in 1932 with Rosenwald's death, they had built 5,300 schools across 15 states.

By 1928, one in five schools for Black students in the South was a Rosenwald school, serving more than 600,000 students. These weren't just buildings—they were symbols of hope and self-determination in communities that had been systematically denied both.

The schools were modern for their time, well-equipped with books, furniture, and learning materials. Teachers received guaranteed minimum salaries, new homes, and opportunities for professional development. For the first time, quality education was within reach of marginalized Black communities at an unprecedented scale.

The Rosenwald program required something remarkable: shared investment. One-third of the funding came from philanthropy, one-third from local education officials, and one-third from the Black community itself.

Following Washington's example at Tuskegee, where students made bricks and built their own learning spaces, Black community members physically and financially constructed the schools their children would attend. This created an extraordinary level of engagement that went far beyond today's concepts of parent "involvement."

Unlike contemporary school systems, where parents can only elect school board members who often serve bureaucratic interests rather than their communities, Rosenwald parents had direct power over their schools from the very beginning. They could define education for themselves and their community.

Did the Rosenwald schools actually work? According to rigorous research by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the answer is a resounding yes.

The study found that the Rosenwald Rural Schools Initiative explained 40 percent of the narrowing of the racial education gap during the period between the world wars. The program also stimulated migration to better labor market opportunities in the North.

The researchers concluded that the initiative "highlights the large productivity gains that can arise when substantial improvements to school quality and access are introduced to relatively deprived environments." The effects were especially pronounced in communities with the worst pre-existing educational conditions.

Lessons for Today

The Rosenwald schools offer powerful lessons for contemporary education reform debates. They demonstrate that partnerships between communities and philanthropists can create meaningful change—but only when those communities maintain real control over their educational destinies.

Too often, modern reform discussions ignore this history. Anti-reform voices want to maintain control of traditional systems that have consistently failed marginalized communities. Reform proponents want to create new systems that they still control, offering only limited participation to the communities they claim to serve.

Neither approach recognizes what the Rosenwald schools proved: that Black and brown communities can and should be the owners, not tenants, of their own educational systems.

As Stephanie Deutsch writes in "You Need a Schoolhouse," Black students often walked miles to their Rosenwald schools, sometimes passing school buses carrying white children to better-equipped schools. But when they arrived, they found "a haven from prejudice" with loving, supportive Black teachers and principals who knew their families and communities.

These schools were more than buildings—they were "collectively built assets that inspired communal aspirations and accountability." They showed what was possible when communities were empowered to solve their own problems.

A Call to Remember

The Rosenwald schools remind us that "public education" has taken many forms for Black Americans throughout history. We must resist letting others define what educational justice looks like for our communities.

The lesson is clear: marginalized communities are not the problem to be solved—they are the solution waiting to be empowered. The systems that exclude them are the real problem.

As we continue to fight for educational equity, it would be beneficial to remember this history. It shows us that the path forward isn't just about reform or resistance—it's about communities reclaiming the power to educate their own children.

The Rosenwald schools prove that when communities are given the resources and authority to build their own solutions, extraordinary things can happen. That lesson remains as relevant today as it was a century ago.